The Dickin Medal

The Dickin Medal

by Tiaan Jacobs, DWD, January – February 2012

My interesting hobby of collecting and researching medals, i.e. includes an interest in animals that served with the Armed forces and the Civil Defence units during World War II. The Dickin Medal, was instituted in the United Kingdom by Mrs Maria Elizabeth Dickin CBE, founder of the People's Royal Dispensary for Sick Animals (shortly known as the PDSA – a British veterinary institution).

As a young woman, Maria Dickin worked to improve the dreadful state of animal health. She wanted to open a clinic where people living in poverty, could receive free treatment for their sick and injured animals. Despite  the scepticism of the establishment, Maria Dickin opened her free 'dispensary' in November 1917. It was an immediate success and she was soon forced to find larger premises. Within six years this extraordinary woman had designed and equipped her first horse-drawn clinic and soon a fleet of mobile dispensaries was established. PDSA vehicles soon became a comforting and familiar sight throughout the country.

the scepticism of the establishment, Maria Dickin opened her free 'dispensary' in November 1917. It was an immediate success and she was soon forced to find larger premises. Within six years this extraordinary woman had designed and equipped her first horse-drawn clinic and soon a fleet of mobile dispensaries was established. PDSA vehicles soon became a comforting and familiar sight throughout the country.

Clinic of the PDSA

She was also aware of the incredible bravery displayed by animals on active service and the Home Front. Inspired by the animals' devotion to man and duty, she introduced this special medal in 1943, specifically for them, which was later popularly referred to as "the animals Victoria Cross" (VC). It was awarded in order to honour any animal displaying conspicuous gallantry,  outstanding acts of bravery and devotion to duty associated with, or under the control of, any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence units during World War II and its aftermath. The award, which can only be considered upon receipt of an official recommendation, is exclusive to the animal kingdom and traditionally, the medal is presented by the Lord Mayor of the City of London.

outstanding acts of bravery and devotion to duty associated with, or under the control of, any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence units during World War II and its aftermath. The award, which can only be considered upon receipt of an official recommendation, is exclusive to the animal kingdom and traditionally, the medal is presented by the Lord Mayor of the City of London.

The Dickin Medal is a large, bronze medallion. The obverse of the medal bears the initials "PDSA" at the top, the words "For Gallantry" in the centre and the words "We Also Serve" underneath, all within a wreath of laurel. The reverse is blank for inscribing with details of the recipient. The medal ribbon is green, dark brown and pale blue, representing water, earth and air to symbolise the naval, military, civil defence and air forces.

The Dickin medal

Of the 54 Dickin Medals awarded between 1943 and 1949, 32 were presented to pigeons, 18 to dogs, 3 to horses, and believe it or not, 1 to a cat.

In 2002 the medal was revived and since then recipients have included dogs who worked in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorism attacks in America in 2001 and dogs serving in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Sixty-three PDSA Dickin Medals have been awarded to date. The citations on the Roll of Honour's are a moving and unique insight into the role animals play in the service of man in times of war. The animals who  have won this award, and whose gallantry has been honoured, must stand as representative of the many through history, equally deserving, whose value and service to man have passed unmentioned.

have won this award, and whose gallantry has been honoured, must stand as representative of the many through history, equally deserving, whose value and service to man have passed unmentioned.

The remarkable deeds of courage, fidelity and endurance performed by dogs in war and in peace, would fill volumes. During World War II eighteen were nominated to receive the award of the Dickin Medal in recognition of their outstanding service. Many countries have had famous war animals, but one remembered specifically by me since my childhood, was Antis, an Alsatian dog, belonging to Czech airman Václav Robert Bozdech, that had received the highest honour given to animals. We must remember, however, that for each animal we know and rejoice about, there are still many unsung heroes in the world that deserve our gratitude and respect and who will never get the recognition that they deserve.

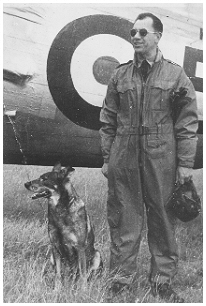

Owned by a Czech airman, this dog served with him in the French Air Force and RAF from 1940 to 1945, both in North Africa and England. No. 311 Squadron RAF was a Czechoslovakian-manned bomber squadron of the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. It was first formed at Honington on 29 July 1940, equipped with Wellington I bombers and crewed mostly by escaped Czechslovakian aircrew.

Bozdech and Antis

Antis' exploits earned him the distinction of being the first Foreign dog to receive the Dickin Medal, the eqivalent of the Victoria Cross, for bravery and outstanding service during World War II, as far back as 1949. Date of award - 28th January 1949. Between 1940 and 1945 Antis served with his owner in the French Air Force in North Africa and with the Royal Air Force in England and accompanied his owner, part of a six-man crew, on more than 30 bombing missions over occupied Europe and Nazi Germany, evading formidable German defences, always lucky to make it back. As his and his owner's fame grew, Antis went from being a valued mascot for his crew, to a symbol of courage for all in the RAF.

Between 1940 and 1945 Antis served with his owner in the French Air Force in North Africa and with the Royal Air Force in England and accompanied his owner, part of a six-man crew, on more than 30 bombing missions over occupied Europe and Nazi Germany, evading formidable German defences, always lucky to make it back. As his and his owner's fame grew, Antis went from being a valued mascot for his crew, to a symbol of courage for all in the RAF.

On March 15th, 1939, German troops entered Czechoslovakia, and Hitler proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a Nazi protectorate. Many in the Czech Air Force began fleeing the country with a common purpose to serve abroad. Among them, was 27-year-old Czech airman Václav Bozdech. Like many of his compatriots, he escaped first to Poland, then to France, where he served in the Foreign Legion, and later as a flyer. It was on one of his missions over France that he found the dog. The moment is described in Freedom in the Air - A Czech Flyer & his Aircrew Dog, by author Hamish Ross. From Glasgow, the author told that there are two versions of the story.

“The earliest version is from a British newspaper of 1942 saying that Bozdech's plane went down in no man's land in March 1940. According to the paper, the airman found the German Shepard puppy in an abandoned farmhouse which had been recently deserted and he took him. He not only saved the dog's life but provided  his squadron with a very lucky mascot.

his squadron with a very lucky mascot.

The second version was in Czech, in Rozlet published in 1945: it said Bozdech bought the puppy from a farmer. We don't really know which version is correct, but certainly the bonding between the two seems to suggest it was something more dramatic than just getting him from a farmer. Bozdech himself subscribed to the earlier version.”

The airman escaped from France with the puppy in tow, eventually making his way to Great Britain. Although strict quarantine laws were in effect, he managed to smuggle his four-legged companion in, and as a result, the dog was raised and spent most of his life on air bases. Bozdech trained the dog well within the No. 311 Czechoslovak squadron and their attachment was great, so great that ahead of one mission, the Alsatian (who could no longer stand to be parted form his owner) stowed away on the plane, the C for Cecelia, the crew's Wellington bomber.

Hamish Ross once again: “He was surprised to find that the dog was not waiting to see him off before the flight and off they went. He just assumed the dog was in somebody's hut and wasn't worried. As the plane was crossing the Dutch coast at about 12 thousand feet, he felt this tap at his elbow. He thought it was the navigator asking for a radio fix on their position, but when he looked in his direction, he saw the navigator was busy in his charts. So he stared into the darkness and couldn't believe it, it was the dog, lying on the floor, his sides heaving as he was struggling to breathe! So he had to share his oxygen mask! “That flight itself was a difficult raid: they had more than their share of enemy activity and there were also lightning storms and several of the radios and some of the electronics were put out of action. When they returned, the Wellington crew came to the conclusion that Antis had brought them luck. And it was the collective decision by the six men in the crew, that Antis would join the combat team.”

Bozdech and his crew

Each time they took to the air, the dog lay still and quiet in the cockpit, inches from Jan's feet. It was not the safest seat on the plane and Antis was injured several times by enemy gunfire but he never complained and was always eager to fly again.

Flying with the dog, was of course strictly against regulations, nevertheless, Antis took part in some 30 missions, bringing inspiration to his crew. Twice, he was injured by flak, once a scratch to his ear and muzzle, another time a chest injury far more threatening. Nevertheless, the animal's nature and training saw him behave exceptionally: it was only on their return from one of the flights that Bozdech realised the animal had even been hurt.

“He said that the dog there showed courage that perhaps a human being couldn't show. The dog did not panic, it did not whine, it just lay at his feet. In 1949, when Field Marshall Archibald Percival Wavell, who was the commander of British Army forces in the Middle East during the Second World War, pinned the Dickin Medal on his collar, he remarked ”that Antis had inspired others through his courage and steadfastness. That was the remarkable thing.”

In 1949, when Field Marshall Archibald Percival Wavell, who was the commander of British Army forces in the Middle East during the Second World War, pinned the Dickin Medal on his collar, he remarked ”that Antis had inspired others through his courage and steadfastness. That was the remarkable thing.”

As the bombing raids continued, rumours of Antis's existence began to spread. They were of course denied, even though the dog's story became something of an open secret. Eventually the truth came out. But rather than being an “embarrassment” for the RAF, Antis with Bomber Command became an inspiration for many. By then his flying days were over, but a dog capable of braving dangerous flights through blinding searchlights and anti-aircraft fire as well as enemy fighters, was a hero and a worthy mascot.

As the conflict wore on, slowly the scales tipped in favour of the Allies. When the war ended in May 1945 it meant that Václav Bozdech and compatriots, including Antis could now soon return home to his native Czechoslovakia. . It had been a difficult six years of sacrifice. But now democracy in Czechoslovakia could be restored.

Unfortunately, their first taste of peace didn't last long. Tragically it would be short-lived: the country again descended into darkness in 1948, this time under the Communists. Overnight, men like Bozdech, who had risked and endured everything for their country, became enemies of the state. After the death of Jan Masaryk, who remained Foreign Minister following the liberation of Czechoslovakia as part of the multi-party, communist-dominated National Front government, it was time–again, to escape and flee. He headed for the border and the freedom of England. For Bozdech that meant a personal tragedy: he left behind a wife and baby son.

Hamish Ross again:

“Of course, the thing to note from the start was that Bozdech couldn't possibly take his wife and a seven-month old child along. But he could take the dog. That wasn't just sentimentality: he did feel that the dog could alert him to danger in advance.”

In fact, the dog was to play a pivotal role in the airman's escape, substantially helping him and two others to escape across the frontier and slip into West Germany. A group of strangers – nearby in the dark – was not so lucky. “The crossing spot was compromised and the searchlights came on. Machine guns from a fixed position raked the ground and these others were either killed or wounded. So Bozdech and his companions then took a round-about route, and the dog was their ‘guiding light' and crossed safely over the border.”

Bozdech never returned to the country of his birth. He remarried in England and had a second family. But also he never forgot what he had left behind. The outcome must have haunted him deeply.

“They fought not only for the freedom of Czechoslovakia but for the freedom of the western countries. Then in '48, when they fled again, those who were able to get out, there was just no hope left. There was just nothing, there was no intervention. For Bozdech it meant complete severance from his country for the rest of his life. He tried very hard to keep in touch with his son Jan, who was by then ten or 12, up until he was around 20, sending him parcels under an assumed name at Christmas.

As for Antis, Bozdech's famous dog? The brave Alsatian lived until the age of 13. After the animal died, Václav Bozdech never wanted - and never had - a dog again.

Today we salute the memory of Maria Dickin, CBE and the Peoples Dispensary for Sick Animals. Maria will be remembered as one of the great figures in the history of animal welfare.

The PDSA also made provision for a last resting place for many of the animals who died after receiving the Dickin medal. You could be mistaken for thinking you have stumbled upon a long forgotten village cemetery : the ancient trees overhanging a meandering path that winds between the moss covered gravestones certainly give that impression. One of the PDSA's most treasured possessions lies in quiet corner of a field in Ilford, North London. The PDSA Animal Cemetery is the final resting place for over 3,000 animals, including 12 heroes awarded the PDSA Dickin Medal for their gallantry in WW II. Today the PDSA cemetery, is a much more mature place… Epiloque”

One of the PDSA's most treasured possessions lies in quiet corner of a field in Ilford, North London. The PDSA Animal Cemetery is the final resting place for over 3,000 animals, including 12 heroes awarded the PDSA Dickin Medal for their gallantry in WW II. Today the PDSA cemetery, is a much more mature place… Epiloque”

Even before I opened my eyes for the first time, the Jacobs household had an Alsation dog, called Plato. He was extremely fond of my mother and would follow her wherever she went, always ready to protect her with his life.

His successor, Nikita Krushshev, was named after the Prime Minister of Russia, 1958 – 64. She was a registered white German Shepard and her grandparents were imported from Russia – she was a real aristocrat...

Last, but not the least, shortly before I left my parent's house in Nylstroom, Northern Transvaal to marry in 1974, my parents got Alsation the third, Antis – so called after my youth animal hero, on my request.

- Hits: 20777